Latest news & resources

Healthy eating when eating out: Why credible nutrition advice matters

Recent data from UK Hospitality shows 60% of diners actively look for healthier options when dining out. This shift has accelerated since COVID, as people have become

Hydration and Menopause: keeping your bladder happy

Is your bladder running your life? Do you need to go to the toilet frequently, or get up during the night to pee? Or do

Supporting menopause in the workplace

Menopause affects everyone in the workplace, either directly or indirectly. Whether it’s the individual going through the menopause transition, or colleagues, family members, and partners,

Women’s health and menopause resources – Get informed and feel empowered

Information and advice around menopause has surged in recent years and there’s a lot of nutrition information available from books and online. It can be

Menopause and collagen: should it be part of your daily routine?

The number of collagen supplements available seems to have increased in recent years. Many of these are marketed to menopausal women. The question: Should I

Menopause and Sleep: Nutritional strategies for better rest

Why does perimenopause impact my sleep? If you are going through menopause, you may find you don’t sleep so well. Well, you are not alone.

Rapeseed oil: Nutrition, health benefits and how it’s made

The rapeseed plant comes from the same family as broccoli, cabbage and cauliflower. It originates from the Mediterranean and Northern Europe. Rapeseed crops have been

Combat perimenopausal fatigue: Essential dietary tips for more energy

There can be a number of reasons for lacking energy and motivation for doing anything. Common perimenopause symptoms such as struggling to get enough good

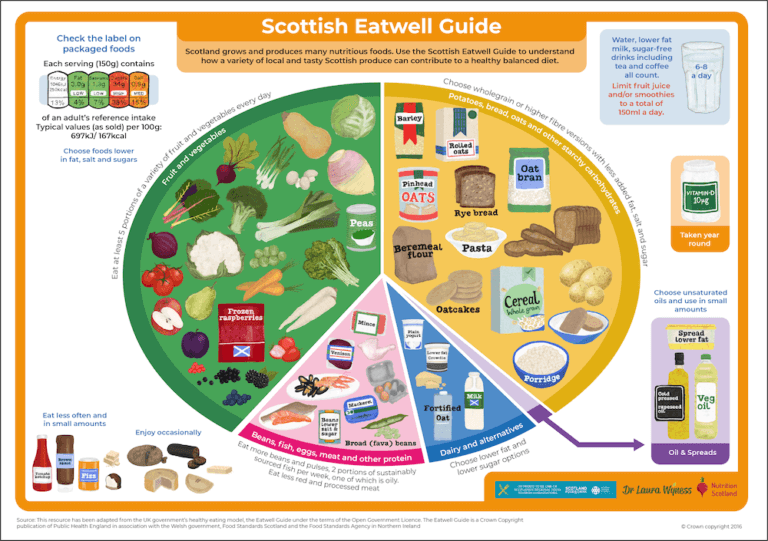

The story behind the Scottish Eatwell Guide

Scottish Regional Food Tourism Ambassador, Dr Laura Wyness and community nutrition social enterprise Nutrition Scotland, have developed the first ever Scottish version of the UK’s